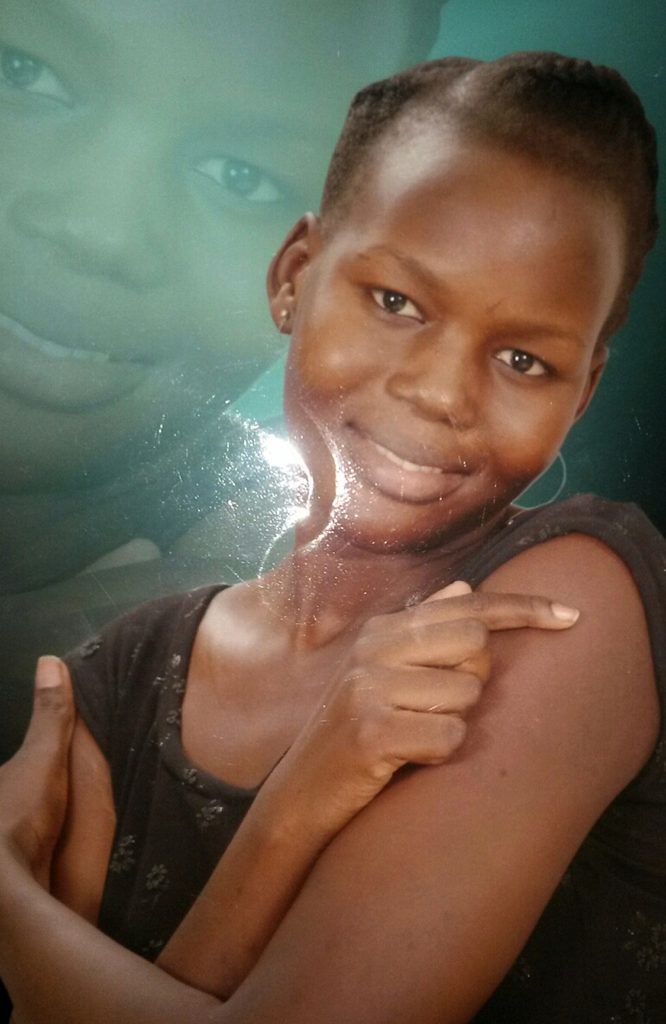

A divorced mother of four, Jan-Juba Arway is about to earn a master’s degree at Syracuse University. She knows she’s ostracized in her own Sudanese community, and she’s OK with that.

A high-risk pregnancy and 38-hour drive pushed Jan-Juba Arway to divorce her abusive husband, despite knowing she’d be ostracized in her community because if it.

By Stacy Fernández

It’s Christmas in May in Jan-Juba Arway’s house. A “Happy Holidays” decal adorns a wall in the living room with five stockings around it, one for Arway and each of her kids. A Christmas tree topped by a glittery gold star anchors a corner of the room.

Last month was Christmas in April, and before that, Christmas in March. It’s not a tradition. With four kids and a thesis to write, Arway just hasn’t had time to take it all down.

“I’m doing all this by myself,” said Arway. “There’s no man living in this house, and we still have the lights on.”

The kids come home from school and beeline for the kitchen. The microwave whirs, dishes clank, and everyone prepares snacks for themselves. The boys break into a minute of laughter. One of the girls goes to her room to change out of her school uniform. Everyone does chores throughout the week. No clean dishes, no laptop. Messy room, no TV.

“She’s very strict,” said Angel “Booboo” Mil, Arway’s second youngest kid.

“‘Cause you guys don’t listen, that’s why she’s strict,” the oldest, Aluel “Lola” Mil, interjected. “She says do your homework, you do the opposite.”

Booboo said that day was opposite day.

Lola is Arway’s “mini-me.” She makes sure her siblings have eaten, picks up chores they “forget” and calls her mom if anything goes awry. When the kids visit their father for the summer he says being around Lola is like having his ex-wife in the house.

Lola, now 15, is also the same age her mother was when she got engaged.

Arway fled her homeland of South Sudan with her family when the country’s second civil war broke out. With the help of Arway’s older sister, the family relocated to Egypt.

It was there, when Arway was getting ice cream from a store, that the future father of her kids saw her and followed her home. He went back later with his elders to ask Arway’s parents for her hand in marriage. In Sudanese culture men don’t “talk to the girl first, you talk to her parents,” Arway explained.

Three months later they were married. When Arway was 16, she gave birth to Lola. Shortly after, her family moved to Arizona to join her sister, who sponsored their visa.

“It wasn’t hard when we moved here because I had a family, I had my sister,” Arway said. “The hardest part was the language.”

When Lola was an infant, Arway tried to frantically explain in Arabic to a 911 operator that her baby was teething and having a fever. All she could get across was, “Baby! Baby!”

Too old to enroll in high school and with English as a Second Language classes at capacity, Arway learned English the same as her daughter — watching subtitled episodes of Barney & Friends.

Arway’s relationship with the father of her kids was like “walking through fire.” He dictated the way she’d dress, where she’d go and who she’d speak with. Her mother and sister were on the no-call list.

“That’s how marriage is,” Arway’s mom told her.

When Arway became pregnant with her fourth child her doctor said she needed to reduce stress due to a high-risk pregnancy. Miscarriage or stillbirth was a possibility.

Arway had to leave. Looking at Google Maps, she found Rochester, New York, a 38-hour drive from Arizona. She thought it seemed far enough. So she packed the van with her three kids, $300 and drove for three days straight.

“I knew he wouldn’t find me here,” she explained to the women’s shelter who helped her in Rochester.

Aiden “Yai” Mil was born on Halloween in 2010. After his 6-week checkup, Arway returned to Arizona to divorce her husband. In Sudanese tradition, divorce is almost unheard of; once you break the marriage, community trust and respect also get broken. But Arway couldn’t let her kids, especially her daughters, grow up thinking their parents’ relationship is what marriage is supposed to be.

After leaving her husband, Arway went after an education. First, a GED, then college full time. She earned associate and bachelor degrees in criminal justice. Aiming at a law program, Arway moved to Syracuse with her kids, but she ended up at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University because of a bet. She came out $100 richer, and this summer she’s expected to receive her master’s in public relations.

Arway has no family in Syracuse. Leaving behind her mother and sister — her “tribe” — was the most difficult decision she had to make. Though Arway is active in the Sudanese community in Syracuse — she works with the nonprofits New American Women’s Empowerment and Empower Interpretation Services of CNY — she’s an outsider.

Arway says she has one friend in Syracuse, a woman her age with an open-minded husband. People keep their distance from the divorcee. She said husbands tell their wives they can’t befriend Arway because she’d be a bad influence.

To them, “I’m a Jezebel.” In modern terms, “a thot,” she says, bursting into laughter.

Arway doesn’t regret her decision. She made them thinking of her kids, of how she could make them proud.

“I can’t tell them to pursue college education when I don’t have college education. I can’t tell them not to be in an abusive relationship when I’m sitting right here and they growing up in this situation. I cannot tell them anything. It will be hypocrisy.”

“You just gotta create your own tribe, and fortunately I have,”Arway said. “I have people here. My house is never quiet.”

Standing in the kitchen, one of the few common spaces devoid of Christmas cheer, Lola calls her mom an inspiration. But, she doesn’t want to be like her.

“I want to become an OB-GYN,” Lola said.