From a refugee camp to her own classroom, a Somali woman aspires to teach

Hamdi Farah lived in a Kenyan refugee camp for the first 12 years of her life before settling in Syracuse with her family. At first, she struggled in school but found a passion for teaching refugee children like herself at the North Side Learning Center.

Listen to Hamdi Farah talk about how she found her passion for education by drawing on her own struggles with learning English in the classroom.

By Mary Catalfamo

Hamdi Farah knew in college that she wanted to be a teacher for the younger refugee children in Syracuse’s Somali-American community, but she had doubts about the idea. How could she teach them English, for example, when she wasn’t always sure of correct spellings herself?

“Although I wanted to help kids and teach kids, I was always afraid of saying I wanted to be a teacher because I thought I was never good enough,” she said.

She recalled those earlier fears while sitting in the basement of the North Side Learning Center, a couple of floors below her own classroom. Farah is now the lead middle school teacher for girls at the center, which offers after-school programs for youth, along with adult classes in English literacy, as well as skills like sewing and financial literacy.

Farah, 22, teaches here three days a week, after she is done with her own classes. She graduates from Onondaga Community College in mid-May and plans to pursue her bachelor’s in education.

Farah spent the first 12 years of her life in a Kenyan refugee camp, where her parents met after fleeing civil war in Somalia. Farah describes a happy childhood in the camp; her parents worked and there was always food on the table. She wasn’t always as passionate about learning as she is now though; she said her parents didn’t push her to attend school in the Dadaab Refugee Complex.

“Although I didn’t go to school regularly, my parents did put me in school and I hated it,” Farah said. “So I would always skip school and nobody would say anything to me.”

Farah’s parents only gave her three months’ notice before relocating to the United States. She envisioned living in a country so wealthy that robots would do her chores. “I was devastated that there were no robots to wash my dishes,” she joked.

Farah’s family, which included eight siblings at the time, relocated to Buffalo, N.Y., in March 2009. There was still snow on the ground when they first arrived in the city. She remembers how unappealing the food was. “They were offering us these sandwich, and we don’t really do sandwich. And I was like, ‘Pork! Everything pork!’”

They found Buffalo isolating without a robust Somali community, which Farah said was a jarring contrast to the strong cultural and social networks Somali refugees have in Kenya. Her mother didn’t feel comfortable letting her play outside.

“It just felt like we were locked in a house when we first arrived. Like back in Kenya, I was used to just walking around, running around, playing around all day,” Farah said. “I was more free in Kenya.”

As a student in the United States, Farah said she experienced small acts of racism, and was bullied for how she pronounced English words. So her family moved to Syracuse almost two years later and resettled in the North Side, which has one of the city’s highest concentrations of refugees.

The NSLC, a two-story brick building, opened in 2009 to help the community with resettlement efforts and English literacy. It sits next door to the Masjid Isa Ibn Maryam, a former church that the center bought in 2014 and repurposed as a mosque. Farah said the adult students appreciate having a place nearby to pray during the day.

Syracuse’s immigrant and refugee population grew by 42.5 percent between 2000 and 2014, according to a study that examined economic impacts of that influx. The city’s school district also had the state’s third-highest number of foreign-born students as of 2017, according to data compiled by the group Safe Havens, which advocates for immigrant children.

Mark Cass, NSLC executive director, said that the majority of people who currently use the center’s services are Somalian. He said the center takes a “strength-based approach” in providing services.

“It’s not ‘Oh, these newcomers don’t have anything and we’re going to give them what they need,’” he said. “We have all kinds of abilities and experiences and assets that we want to take care of, take advantage of — in exchange we do provide things they need.”

At the NSLC, Farah said she found a community of other girls from Somalia and a place where she could get extra help with homework from volunteers and teachers who worked at the center. There also wasn’t as much pressure to speak perfect English.

“The other students — they speak broken English like me. So just being able to speak back and forth to each other without anybody making fun of anyone, was really lovely,” Farah said.

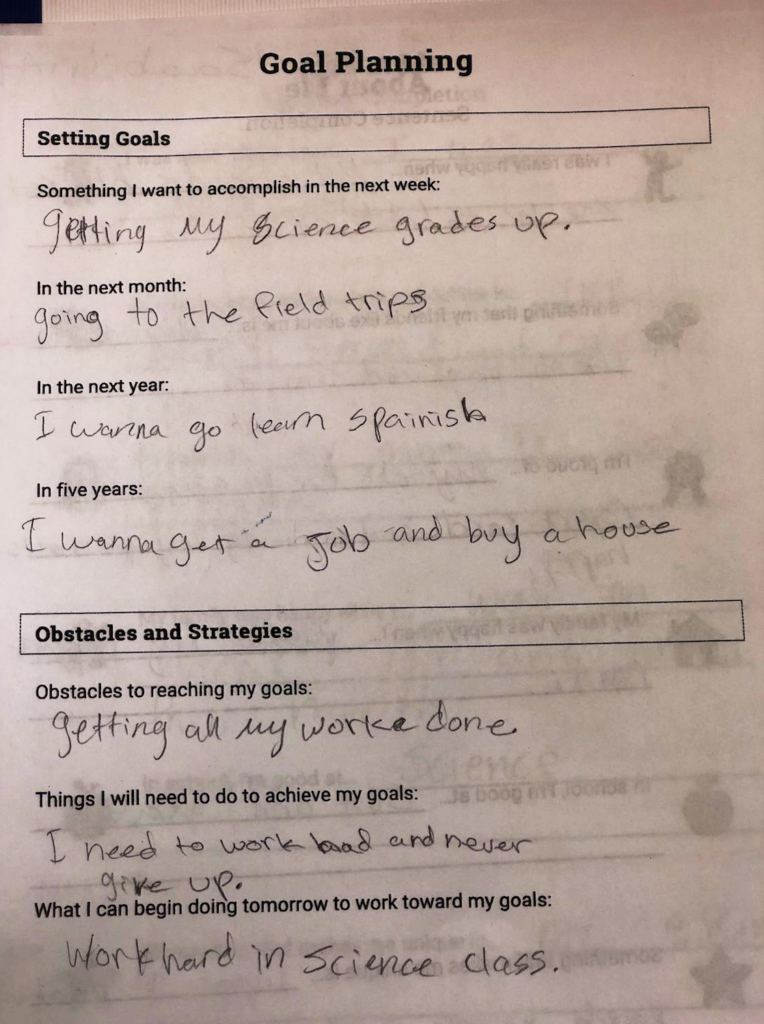

When she entered college, Farah aged out of many off the classes at NSLC but still wanted to be involved. Cass said she started to volunteer and help with writing grants. Farah also participated in the community organizing workshop Leadership Classroom with her peers, who organized a project to get the NSLC a van for field trips and transportation.

Cass said he’s seen Farah continue to grow as a leader and in her own goals for the future. “She’s a terrific example of what we’re trying to achieve,” he said. “That’s what this organization is really about.”

When the teaching position for the middle school girls’ class opened, Farah jumped in, despite her doubts. A normal day in her classroom involves giving students activities in math, reading and writing, as well as helping them with homework. She tries to help her students in more basic academic areas that they may have missed out on, growing up as refugees.

“I started working here and it’s like, you know, you can do this,” Farah said. “Maybe you becoming a teacher will help them set goals that they are scared of maybe to set, maybe dream about dreams that they’re maybe scared about dreaming.”

Farah also asks her students to journal every day. “I feel like that will help them express how they are feeling, maybe leave their day, whatever happened to them at school, whatever that happened to them at home, like, in that journal. And then kind of start out new,” she said.

When she looks to the future, Farah thinks of her childhood friends who still live in the refugee camp. “Those students don’t have the same opportunity that I have. It would be unfair if I don’t take advantage of that opportunity,” Farah said. Being the first in her family to graduate college, Farah said she feels a lot of pressure to do well in school and succeed.

“No matter how many times I fail, no matter how stressed I am, whenever I come to my classroom and see those girls motivated, see them wanting to do more in life, it motivates me,” Farah said.